To Practice or Not to Practice 10,000 Hours

To practice 10,000 hours or not to practice 10,000 hours. That is the question. (And no, we aren’t singing a Dan & Shay song).

Does Malcolm Gladwell, author of the best-selling book, Outliers or Dr. K. Anders Ericsson, internationally renowned psychologist, get it right? Did Ericsson say the number of hours is essential to gain the knowledge and expertise, which Gladwell then translated into 10,000 hours to master a skill to become an expert? While the 10,000-hour theory has been technically debunked, can it or does it still hold true?

One can believe that practicing any skill – free throws, ground balls, math equations, dance moves, or suturing – can lead to expertise, but does that mean you’ve become a literal expert? Can one not argue that it has to do with the quality of the practice vs. the quantity that leads to competence and then to expertise? Put it to you this way, if you practice a skill, over and over and over, but your technique is horrendous – but you’ve put in the time, the hours – are you an expert?

Harrison Smith, from The Washington Post states, “Dr. Ericsson argued that the way a person practiced mattered just as much, if not more than the amount of time they committed to their craft.”

So, let’s talk about “traditional” practice, “purposeful” practice, and what Ericsson refers to as “deliberate” practice.

In a traditional practice, you are going through the motions. You have an idea of what you’re doing, you know what you’re trying to accomplish, and you do your best to get to the goal. You’re not focused on the technique; you’re focused on the outcome. Not to say there is anything particularly wrong with this way to practice in certain situations. You are getting better at your skill. Just know that once you’ve hit a certain level, your ability to progress beyond that level will now be limited.

With purposeful practice, you are much more focused on a specific goal, and you are absolutely focused on getting better at your craft. This goal and focus push you beyond your current comfort level - you are unequivocally dialed into achieving better results. You can literally see from your practice where your strengths lie and where your weaknesses are showing. As a learner, you are becoming more and more creative with technique to extend beyond your plateaus and move to the next level.

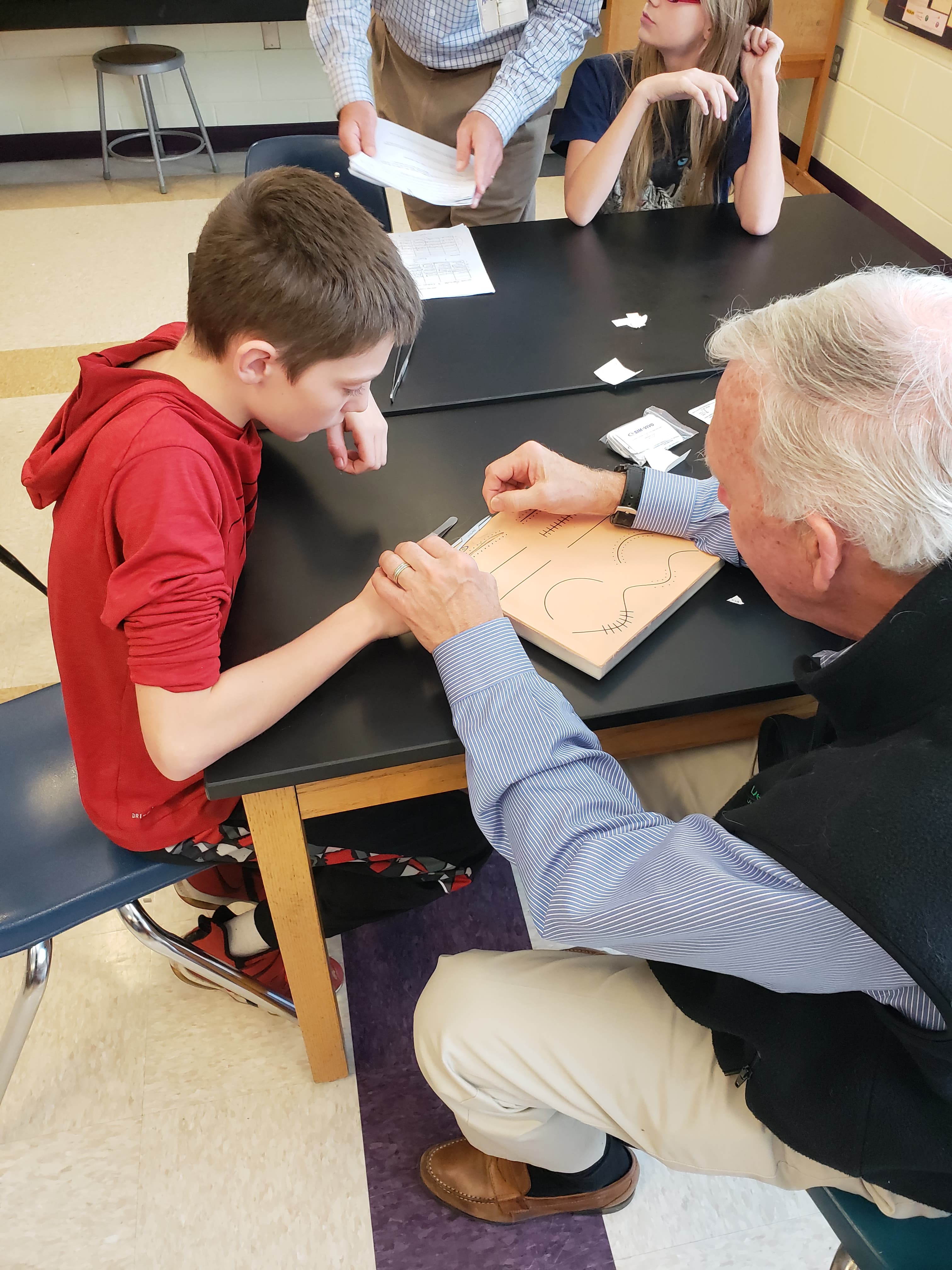

Here’s where purposeful meets deliberate. You maintain that same purposeful practice, but now, you are in a field where it can clearly be demonstrated, beginner vs expert. You have a coach, a mentor, a teacher, or an instructor tailoring your practice to help you meet your goals. This mentor can provide immediate feedback to change the course of your practice.

So, do 10,000 hours of traditional, purposeful, or deliberate practice make you an expert? If it’s traditional, then does 5,000 of deliberate get you there?

Here’s what we do know for sure; you can’t expect to be an expert if you’re just a beginner, hence you must keep practicing! Regardless of the number of hours, it is only through practice that you get better. And it’s not simply practice. It must be purposeful with deliberate practice. Think about all the hours Shaq put in at the free-throw line. Even after all those hours, he retired hitting only 52.7% of his free-throws. Shaq never became an expert at this part of his game. However, he is a Hall of Famer.

Practice where you are focused on the skill, focused on each step of the technique, focused on the anticipated (expected) outcome.

It’s the ability to practice with the right technique to obtain the desired outcome. It’s the ability to know that in your “game situation”, your subconscious, your muscle memory, is going to kick-in, and the desired outcome is going to be what you had anticipated.

This only happens with deliberate practice.

Once you have mastered your skill, do you stop your deliberate practice? Some would argue that once you have become a master, you no longer need to practice with such deliberateness, but rather, you must simply maintain your skills. Meaning, you must still perform the tasks of which you have mastered.

Once Tiger Woods became the number 1 golfer in the world, did he not still use a coach? Did he still not hit the range in the off-season? Did he still not putt in his own backyard regularly? (I honestly don’t know if Tiger putts in his backyard, but I think you catch the message here).

Dr. John Fortune tells the story, “There once was a surgical resident who was exposed to a two-week intensive skills boot camp training program during his first year of training. By the end of the session, he could tie knots with his eyes closed while listening to the Grateful Dead. Two years later, we were attaching a skin graft to a patient’s chin with a 4-0 nylon, and I asked him to tie the suture in place. Watching him struggle with this simple task that he had previously learned so well would have been funny if it weren’t so pathetic. It was clear that he had not practiced his knot-tying skills that he had mastered only a short time ago.”

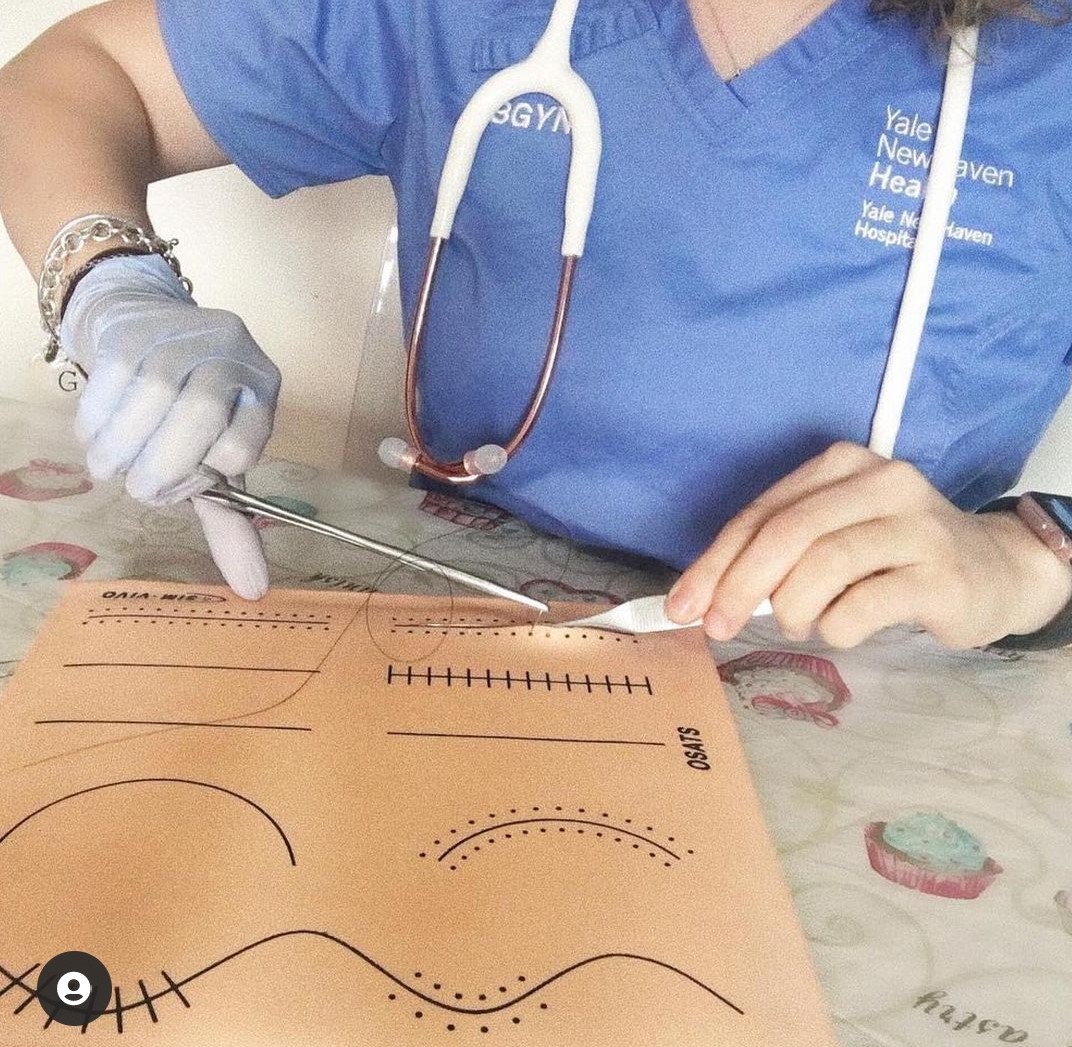

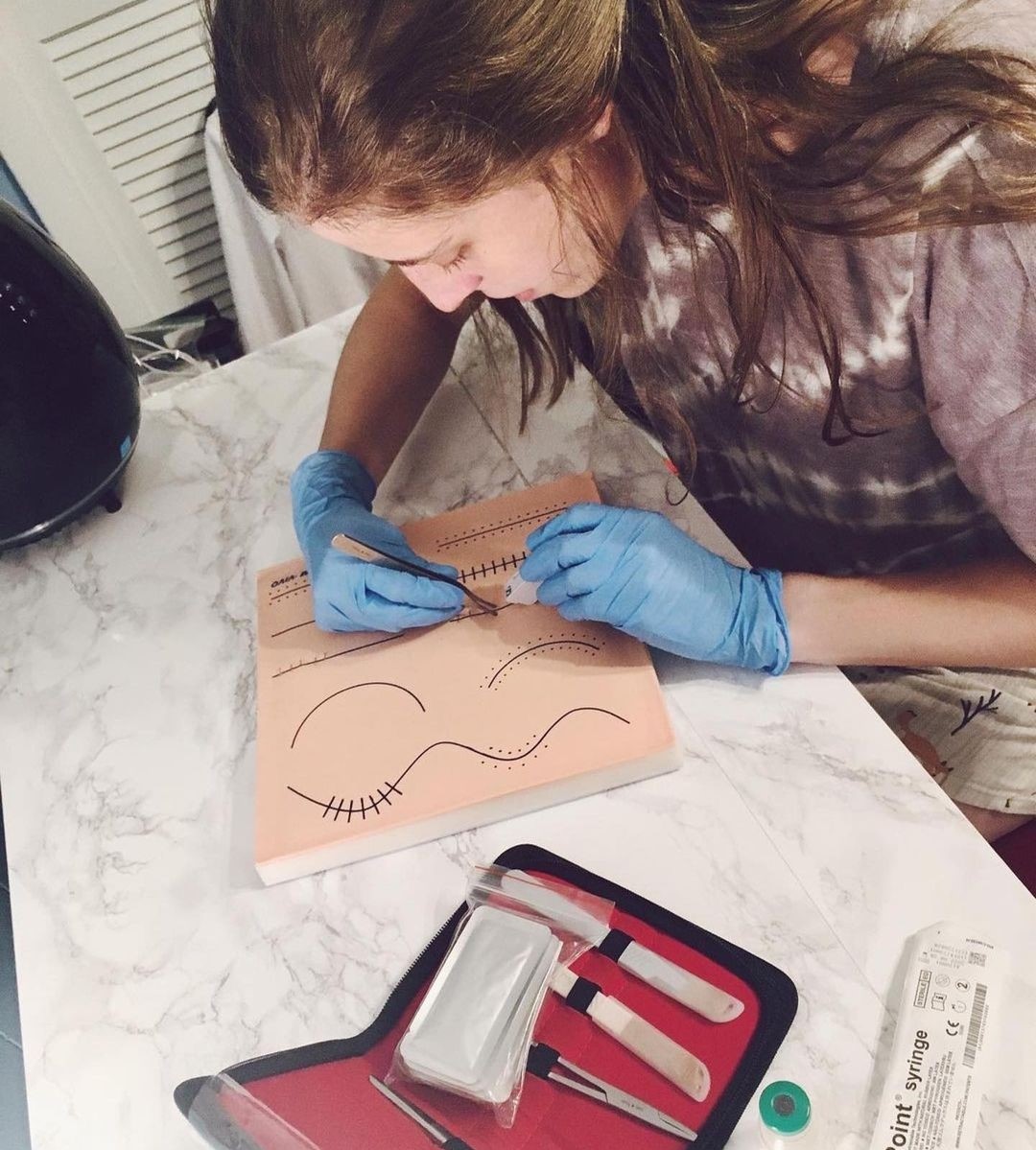

This is precisely why Sim*Vivo was created. Our learning systems allow each learner the opportunity for at-home practice with our Sim*Suture, Sim*Tie, and Sim*Bowel learning modules. These surgical task trainers contain all equipment necessary to learn and practice to competence. Once you’ve reached a level of competence, now is the chance to work more closely with your instructors to truly become a master of your craft.

How will you become an expert at your skill or in your field? What’s your game plan?